Summary

Note-taking activities in physical classrooms are ubiquitous and have been emerging in online learning. We designed a prototype system, NoteStruct, which prompts learners to perform a series of note-taking activities. NoteStruct enables learners to insert annotations on transcripts of video lectures and then engages them in reinterpreting and synthesizing their notes after watching a video. To investigate how these step-by-step note-taking activities affect learners, we conducted a study with a sample of Mechanical Turk workers (N=80), comparing NoteStruct with a free-form note-taking prototype. The results show that although using NoteStruct versus free-form note-taking did not impact short-term learning outcome, learners using NoteStruct produced longer notes. These longer notes were also less likely to include verbatim copied video transcripts, but more likely to include elaboration and interpretation.

Background

Note-taking has been a common activity adopted by learners in online learning [1]. Researchers have investigated the benefits and challenges of note-taking for learners in two aspects: encoding and external storage [2].

Encoding means the process of note-taking can support learning, as it may induce deep cognitive process such as generating self-explanations for a learner’s own understanding, and building connections with prior knowledge [3]. Despite the potential benefit of encoding, many studies have shown detrimental effects of taking notes while learning, as note-taking costs attentional resources that are needed for processing rapid and dense lecture presentation [2]. Being faced with demanding note-taking activities and the learning task at the same time, learners may fail either to comprehend learning materials or to take notes without deep processing.

On the other hand, the external storage function emphasizes the values of reviewing notes. Benefit of reviewing notes (external storage) is widely accepted, but learners often take incomplete notes that are limited for later use.

Digital note-taking seems to be an efficient way to facilitate note-taking by providing affordances (e.g., typing or copy-paste functions) to speed up the recording process. Yet, research has demonstrated that digital note-taking may not benefit learners as longhand note-taking can do because digital note-takers tend to transcribe lectures verbatim instead of processing information in their own words [4, 5].

Altogether, the challenges of note-taking motivate us to explore designs to scaffold note-taking processes and prevent the drawbacks of digital note-taking at the same time.

NoteStruct System

We design NoteStruct to scaffold note-taking while learning from online video. NoteStruct divides note-taking process into three phases in order to reduce interference of note-taking in video watching while preventing learners from mindless transcribing lecture into notes without deeper processing.

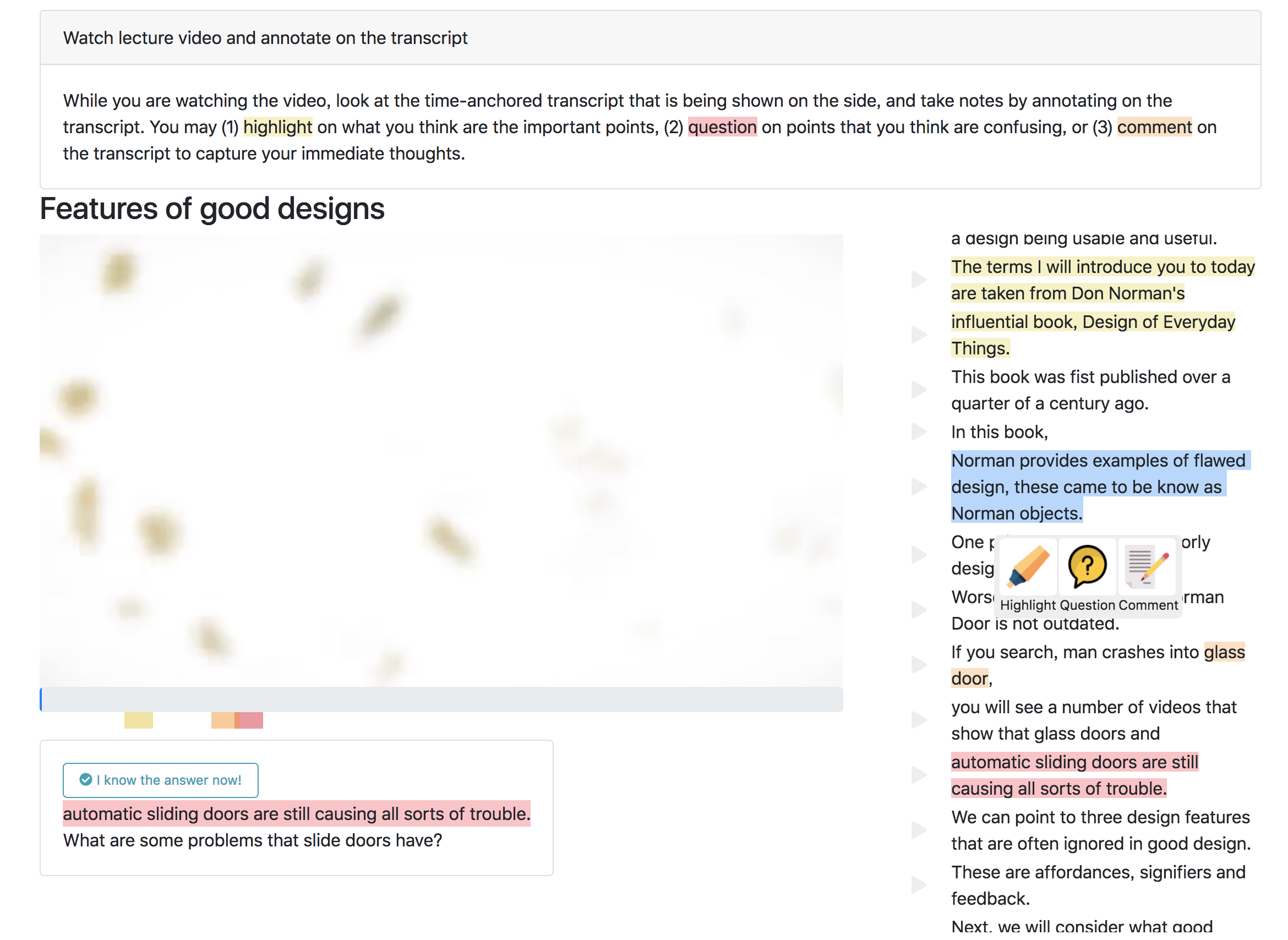

Phase 1: Annotate video transcript with hightlights, comments, questions

First, learners are able to annotate the transcript while watching the video. NoteStruct offers three types of annotation tools on video transcripts: highlighting, commenting, and questioning. Highlighting can help learners recognize and select key points for later use. Commenting allows learners to write down thoughts or ideas, while questioning allows learners to register their confusion about the content. When learners type a comment or question, the system automatically pauses the video, to allow extra time for reflection. If learners add questions, we prompt them to find out answers in later video sections.

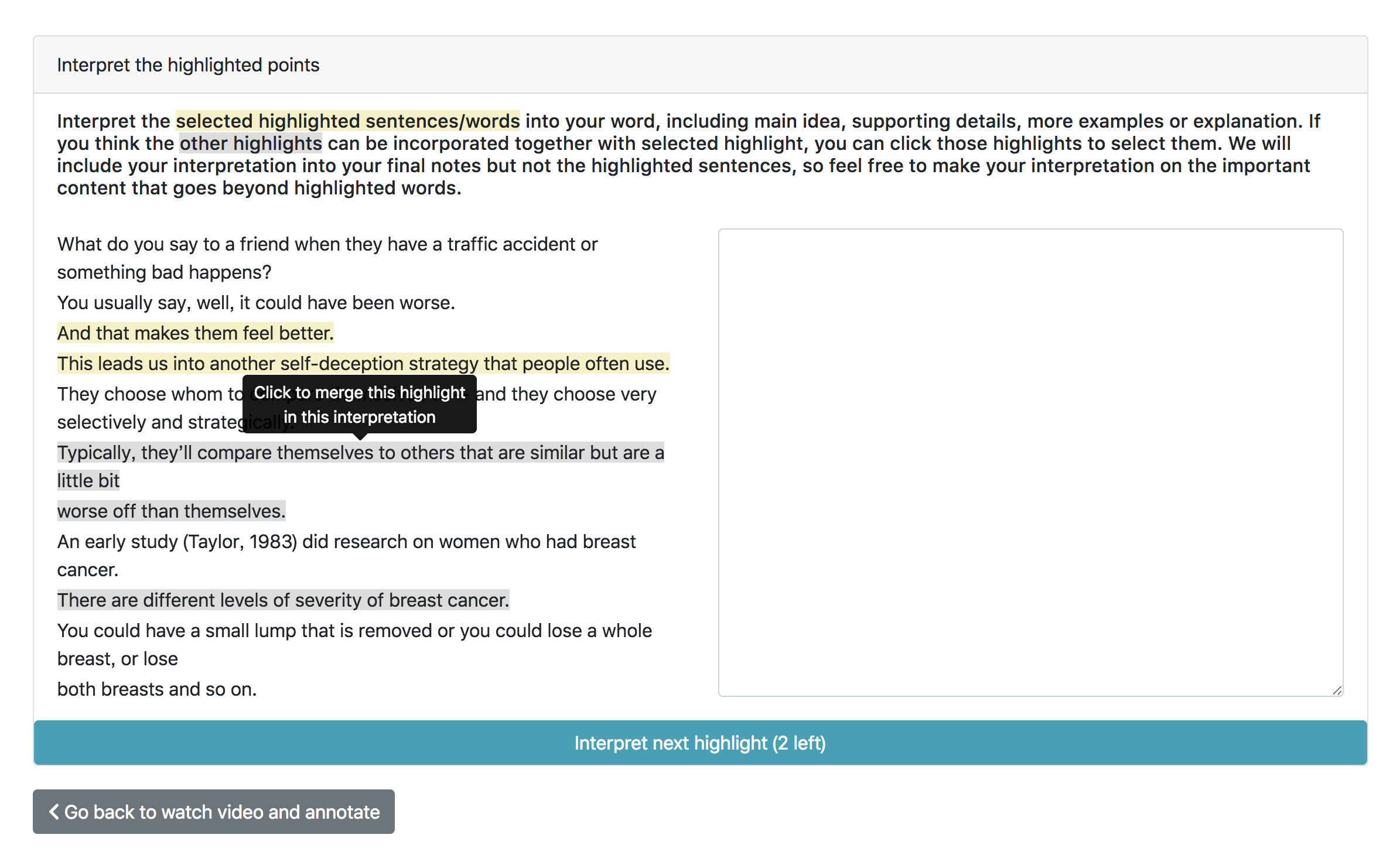

Phase 2: Review and interpret hightlighted sentences in addition to verbatim notes

Second, learners were walked through every highlight they made and asked to elaborate their thoughts, which can be talking about the key concept from their perspective, providing supporting details, giving more explanation or examples. Learners are guided to interpret one highlighted sentence at a time in order to allocate their attention on minimum key points when interpreting, but they can also merge multiple highlights in an interpretation.

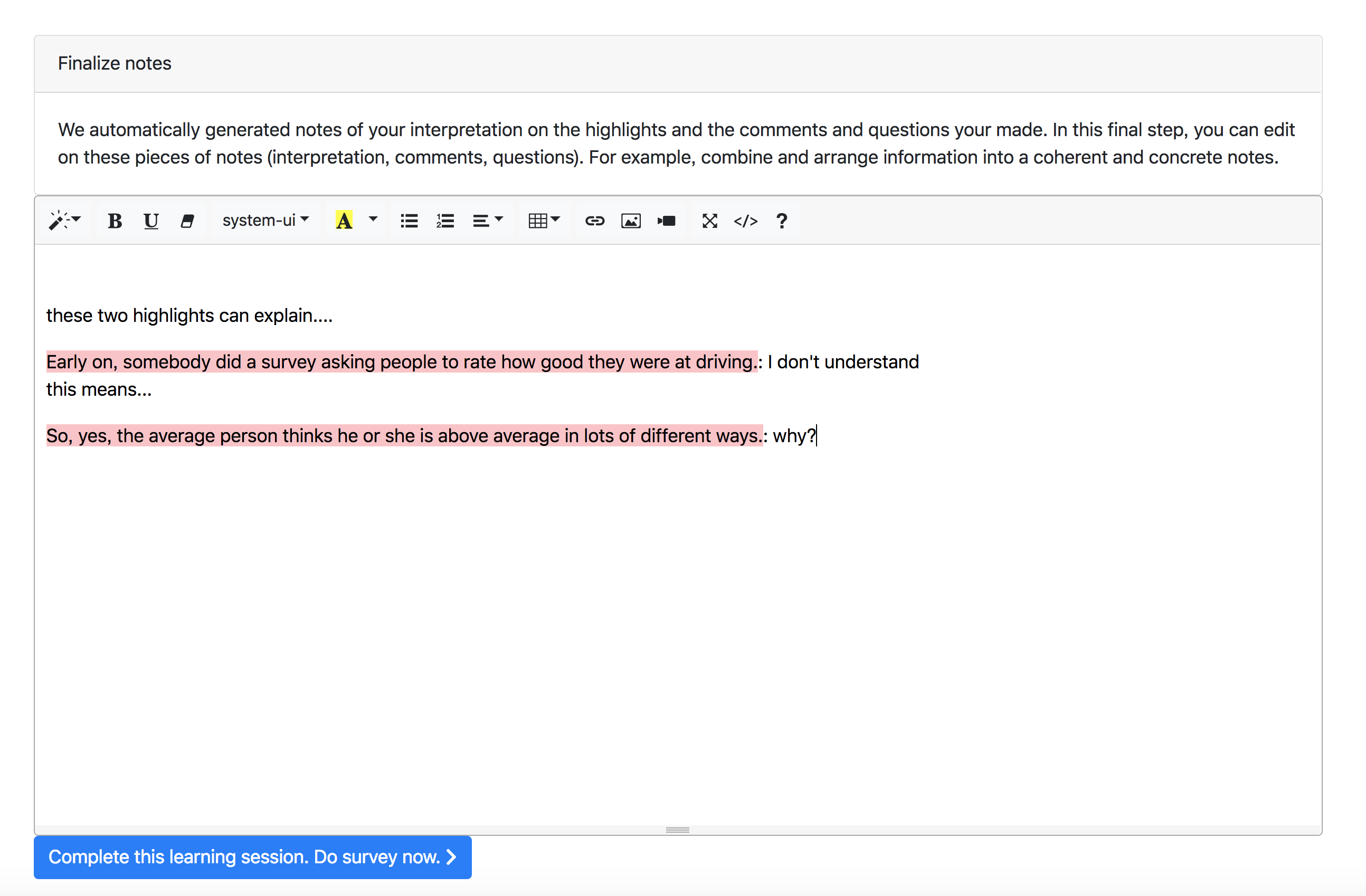

Phase 3: Finalize notes from previous phases with a free-form editor

In the final phase, learners review all initial notes generated in phase 1 and 2 in a free-form text editor, including their comments and questions with the anchored transcript sentences and their interpretations. Learners have the option to add anything else they like, or edit and remove parts from the notes. They were prompted to combine and arrange information into coherent notes.

Evaluation

We conducted a within-subjects experiment on Amazon Mechanical Turk to see if NoteStruct helps learning and note-taking. The study compare NoteStruct against a baseline system. 80 participants were recruited for an approximately 40-minute long online study.

Participants were first guided to visit the NoteStruct website where they received an overview of the study procedure. The procedure included three phases:

- A pre-survey that included demographic items and pre-test questions for two videos.

- Two learning sessions, in which they watched two different, consecutive videos (4 minutes long each). One video was paired with the baseline system, the other with NoteStruct. The pairing and presentation orders of video and note-taking tool were counterbalanced.

- Post-surveys after each learning session, which included post-test questions, and open-ended questions to understand their learning experience.

We measured learners’ short-term learning outcome, perceived learning gain, and also evaluated learners’ notes by number of words, degree of verbatim.

- Short-term learning outcome was measured as the change in accuracy between the post-test items and the pre-test items, and then converted the results within the same video to z-scores.

- Perceived learning gain was calculated as the difference between two questions: (1)“After going through the learning process, how much do you think you have learned from the lecture? 1: Not at all, 7: Fully learned from the lecture”, (2)“Before watching the video, how much background knowledge related to the topic of the video did you have? 1: Not at all, 7: Expert knowledge”.

- Degree of verbatim in notes was defined as percentage of copied one-, two-,and three-grams from video transcripts in the notes.

Results

-

Participants reported significant higher perceived learning gain using NoteStruct.

Participants reflected that by prompting them to review the content several times, NoteStruct might benefit their learning: "...and going through the content multiple times at each stage helped cement my understanding of the topic." They also reported benefits in reflecting when taking notes: "...being able to rearrange my thoughts after the lecture by reviewing each highlight, and I find that taking notes was really useful and then afterwards having to explain the notes again."

-

There was a numerical trend of higher short-term learning outcome for NoteStruct but no significant difference.

This result might suggest process of taking notes with NoteStruct has no impact. On the other hand, 4-minute videos could be too short for testing learning performance. Studies conducted with longer videos or over longer time periods might be needed to detect the cumulative effects of taking elaborative notes or reviewing more complete notes.

-

Participants generated significantly more words when using NoteStruct than baseline interface.

-

Participants generated less copied one- and two- grams in NoteStruct condition, but no significant difference in three-grams between two conditions.

Noted that participants generated much shorter notes in baseline condition, the low copied three-gram fraction of baseline condition is more likely to be a result of abbreviation (e.g., simply noting down concept without explanation) instead of elaboration.

-

Most of the participants appreciated the convenience of annotating a transcript while watching the video , reporting statements such as: "I really liked the in line comments, that was a lot more useful than the first one [baseline interface]". However, some participants still found it distracting: "I was more focused on capturing highlight than what he was saying" and "finding myself ignoring the video to focus on reading the transcript."

Distraction problem was indeed found to be much more severe in baseline condition. Participants found it hard to type while listening to the instructor: "Even though I can type fast, I couldn’t type as fast as she was talking." Thus, they wanted features like that of NoteStruct for quickly capturing notes: "If you could drag the text to the notes section, that might be more helpful than having to type everything, and I would like to be able to highlight notes and have them automatically copy over.".

Even though highlighting on transcript is more efficient than typing to take notes, it can still diverge attention from watching the video. There are two approaches that might further solve this problem. First, we can stop or slow down the video when a learner start highlighting, so that he could focus on the note-taking task without worrying about missing the lecture. The other approach is to minimize the attention cost on hightlighting. For example, instead of placing the whole transcript beside the video we can show a small piece of it on the video (like other video players typically do), while allowing one-click highlight function to facilitate the task.

-

Participants valued the second phase that allowed them to extend their notes: "I like that it had everything that was said and could be highlighted and elaborated upon". They also appreciated the flexibility of the final free-form editing function: "I found it useful that it listed all the information and it was easy to organize the notes."

However, a few reported that note-taking with NoteStruct was time-consuming: "I found the second part of interpreting the highlights a little tedious and long.", and that NoteStruct diverged from their typical note-taking habits: "What could be improved is to let a person take notes the way they are used to".

References

[1] George Veletsianos, Amy Collier, and Emily Schneider. 2015. Digging deeper into learners’ experiences in MOOC's: Participation in social networks outside of MOOC s, notetaking and contexts surrounding content consumption. British Journal of Educational Technology 46, 3 (2015), 570–587.

[2] Kenneth A Kiewra. 1989. A review of note-taking: The encoding-storage paradigm and beyond. Educational Psychology Review 1, 2(1989), 147–172.

[3] Richard J Peper and Richard E Mayer. 1978. Note taking as a generative activity. Journal of Educational Psychology 70, 4 (1978), 514.

[4] Aaron Bauer and Kenneth Koedinger. 2006. Pasting and encoding: Note-taking in online courses. In Advanced Learning Technologies, 2006. Sixth International Conference on. IEEE, 789–793.

[5] Pam A Mueller and Daniel M Oppenheimer. 2014. The pen is mightier than the keyboard: Advantages of longhand over laptop note taking. Psychological science 25, 6 (2014), 1159–1168.